THE LONELY RIDE OF THE HILLBILLY SHAKESPEARE

New Year’s Eve, 1952 arrived with the kind of weather that made even brave people stay home. Snow came down hard and bright, erasing the edges of the world. Somewhere on that frozen map, a powder-blue Cadillac pushed forward through West Virginia night, headlights cutting a narrow tunnel of visibility.

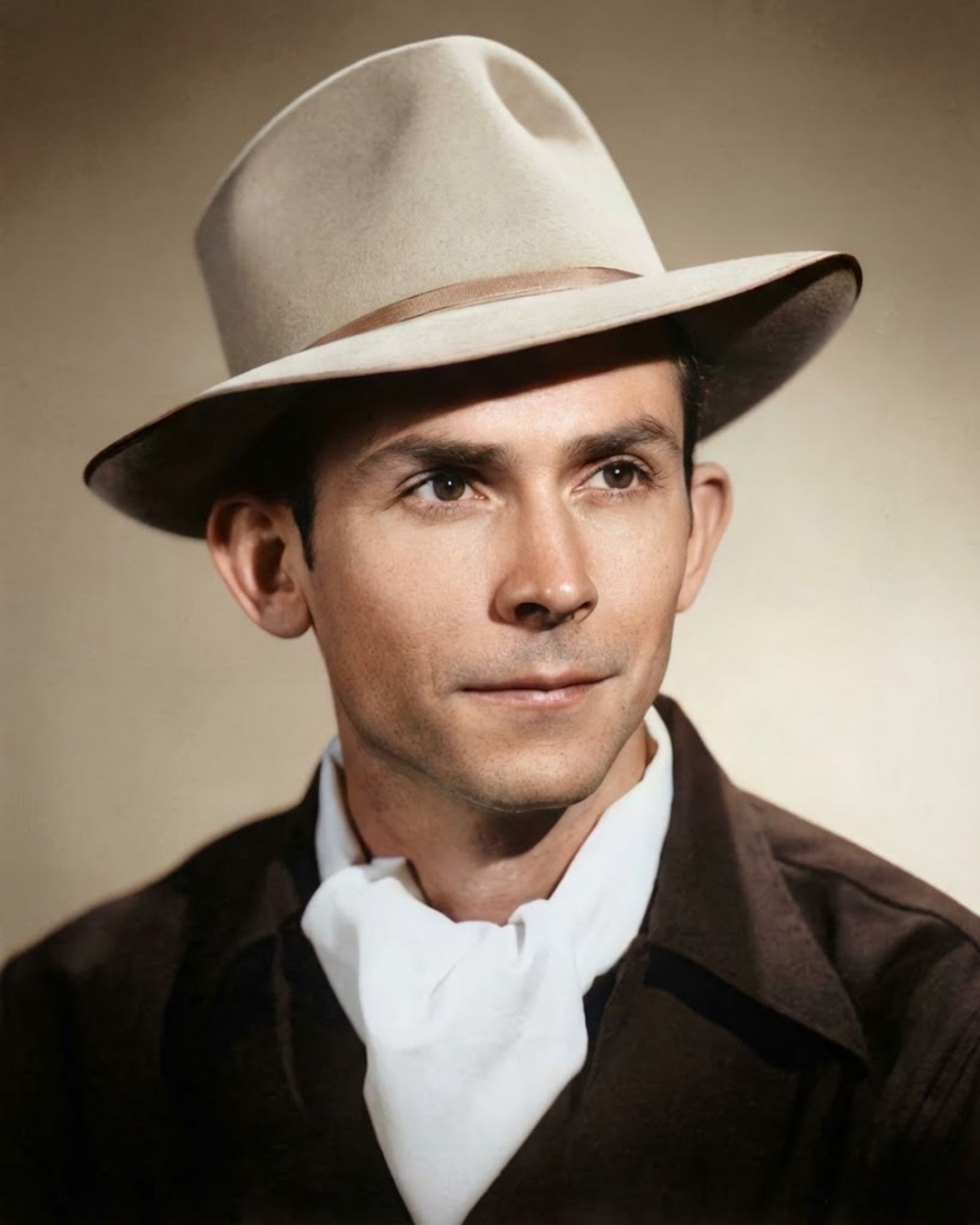

In the backseat sat Hank Williams. Twenty-nine years old. A face that could still look boyish in photographs, yet carried a weariness that felt decades older in person. His suit was neat enough to pass for confidence, but the body inside it had been fighting for years. The pain was constant, the loneliness louder when the crowds went quiet. And on a night when everyone else was counting down to midnight, Hank Williams was simply trying to make it to the next mile.

A CAR, A STORM, AND A QUIET KIND OF FAME

The driver was young, hired to get Hank Williams to the next show, to the next city, to the next obligation that came with being the voice so many people depended on. He kept both hands on the wheel as the Cadillac skated over slick patches. Every so often, he checked the rearview mirror.

Hank Williams wasn’t talking much. He wasn’t laughing like the man fans imagined from the stage. He looked small in the backseat, shoulders tucked inward, as if bracing for another wave of pain. The driver didn’t ask questions. He had learned, quickly, that some silences were not empty. Some silences were packed tight with things a person couldn’t say out loud.

Outside, the storm didn’t care who was famous and who wasn’t. Snow piled up against fences, swallowed road signs, and turned the world into a blank page. Inside the car, the heater fought hard. The radio crackled when it found a station, then faded again. And Hank Williams drifted in and out of sleep, that rare, thin kind of rest that comes when exhaustion finally outruns discomfort.

THE SONGS THAT KNEW TOO MUCH

Hank Williams had a gift that still feels unsettling when you listen closely: Hank Williams could turn pain into plain language without making it sound dramatic. Hank Williams didn’t need fancy metaphors. Hank Williams could say one honest line, and it would land like truth on a kitchen table.

People called Hank Williams the Hillbilly Shakespeare, and it wasn’t just because the songs were clever. It was because the songs felt like they understood people before people understood themselves. Heartbreak, regret, stubborn hope—Hank Williams wrote them like he had been living inside them.

That night, the world outside the Cadillac was celebrating. Inside, Hank Williams was carrying his own private midnight. The driver later remembered how quiet it all was. No grand speeches. No farewell. Just the steady hiss of tires on snow and the occasional glance in the mirror to check on the man who had made a nation feel less alone.

Sometimes the loudest goodbyes happen without a sound.

THE MOMENT THE ROAD STOPPED

Hours passed. The Cadillac kept moving, stubborn against wind and ice. The driver drove carefully, choosing patience over speed. Hank Williams remained still. At first, it felt like the best possible outcome—Hank Williams was finally sleeping, finally getting a break from the ache.

But morning has a way of making the truth harder to avoid.

When the car slowed and stopped, the driver turned to check again. Hank Williams did not stir. The driver called Hank Williams’s name once, then again, louder this time. No response. The stillness wasn’t the calm of sleep anymore. It was a different kind of quiet, the kind that feels wrong even before you understand why.

The driver climbed out into the cold, circled around, and opened the back door. The winter air rushed in like a verdict. Hank Williams was there, slumped where the road had left him, alone in the backseat of that powder-blue Cadillac.

The realization landed slowly, then all at once: Hank Williams was gone.

THE STRANGEST COINCIDENCE OF ALL

As the news traveled, people reached for the familiar details that make tragedy feel comprehensible—where, when, how. But one detail rose above the rest, the one that made even longtime fans pause and stare at nothing for a moment.

At the exact time Hank Williams died, Hank Williams had a number one song sitting at the top of the charts: “I’ll Never Get Out of This World Alive.”

It is tempting to call it a prophecy, because it feels almost impossible that a title like that could be waiting there, like a sign hung up in advance. But the more honest truth is simpler and sadder: Hank Williams had been writing about the edge of things for a long time. Hank Williams wasn’t predicting the future so much as describing a feeling that never let go.

WHAT REMAINS AFTER THE RIDE

The Cadillac ride ended, but the songs didn’t. That is the strange bargain artists sometimes make with time. The body leaves, but the voice keeps showing up—on radios, in diners, in lonely rooms where someone needs a line that tells the truth without judging them for it.

People still argue about what Hank Williams could have been if Hank Williams had lived longer. More records, more stages, more chances to find steadier ground. But there is another question, quieter and harder: how much did Hank Williams already give away just to keep singing at all?

New Year’s Eve, 1952 is remembered as a night of celebration for most. For Hank Williams, it became something else—a final ride through a storm, a quiet ending, and a legacy that still feels close enough to touch. Hank Williams left the world in silence, but Hank Williams did not leave it empty.